Part 1 of 4 in our Aid Leveraging Series.

Aid leveraging has become an “icky” word in some higher education circles. To insiders, it has come to signify the proverbial race to the bottom that is defined by high tuition discounting and low yield experienced by institutions that use outdated one-size-fits-all approaches to undergraduate student recruitment. To those outside institutions, particularly school counselors, access groups, students, and families, it connotes something worse. Aid leveraging, understood as their institutional aid offer, seems like a black hole whereby untold sums of money that would make college more affordable are withheld from deserving students.

Sadly, the truth is that aid leveraging has become a little bit of both. Schools that have been lured by outdated methods of divvying up scarce institutional resources find themselves in an unsustainable financial aid “arms race” that does not yield the results they need and want. Kennedy and Company has worked with several institutions that have had difficult conversations as a result of discount rates that have soared to unimaginable levels. Colleges and universities cannot operate in the red and continue to exist. On the flip side, students and families also should have clear expectations about the aid they can expect to receive from any given institution, or at least be able to find information during their search process from websites, net price calculators, and other tools. The reality is that all but the most elite institutions have limited funds available to assist students, and they desperately try every admissions cycle to put these dollars to their highest and best use.

Modern colleges and universities must operate like a business, no matter how much we would like to believe otherwise. They must be, at the very least, revenue neutral to sustain the important mission of educating our future generations. In the face of declining public investment, costs have been passed on to consumers – students and families. Education is like other major life purchases, housing and automobiles, but it is unlike those commodities. It is an investment in the student’s future. We have accepted that not every person pays the same price for the same new car, and the same is true of education. Students will pay different prices for the same education. This doesn’t have to be “icky” if institutions are up front about the aid process. They should be clear about how they allocate limited aid dollars in alignment with their mission and values and openly share options for students who get less aid than they believe they should have. Schools must optimize their limited funds to enroll students aligned with their mission. Doing so requires that they address both the student and family’s willingness to pay and their ability to pay, and they can and should say this to their prospective students.

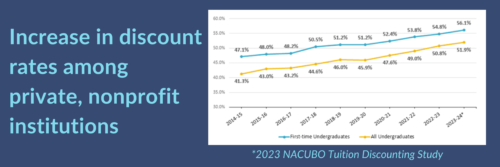

Merit and need based aid play separate roles for just that reason. Our philosophy is driven by the notion that merit aid should be provided as an acknowledgment of a student’s academic performance and other desirable attributes that align with the institution’s mission. In other words, merit aid should reflect how the students see themselves, and how they stack up to others like them. Need based aid, on the other hand, should be provided so that students can afford to enroll, and just as importantly, stay enrolled until they graduate. In traditional aid leveraging models these two have been conflated. The old two-axes grids for awarding aid based on test scores and financial need do not suffice anymore and they have created unsustainable discount rates that threaten the very existence of some lesser funded institutions. A recent study by NACUBO (National Association of College and University Business Officers) found that at participating private, non-profit institutions’ discounts had reached an all-time high of just over 56% for incoming first-year students. Kennedy and Company is aware of some instances of where those rates have reached 70% or more.

The old two-axes grids for awarding aid based on test scores and financial need do not suffice anymore and they have created unsustainable discount rates that threaten the very existence of some lesser funded institutions. A recent study by NACUBO (National Association of College and University Business Officers) found that at participating private, non-profit institutions’ discounts had reached an all-time high of just over 56% for incoming first-year students. Kennedy and Company is aware of some instances of where those rates have reached 70% or more.

There are better ways to allocate institutional resources. Our work with our partners is centered on four pillars – assess, design, build, and support. We begin with understanding the goals, resources, and historical data of our partner institutions. This process allows us to collaboratively align limited funds and create a strategy that supports their goals and institutional mission. Our partnership doesn’t end there, throughout the cycle we remain trusted advisors helping our partners monitor their progress and pivot strategy when necessary. Aid leveraging is a necessity and when done properly, with the right mix of strategy, implementation, and communication, it can achieve institutional goals and support undergraduate students in a sustainable way.

NEXT UP: In our next piece, we will discuss aid leveraging for law school students. Stay tuned for its release in early April.